Let me tell you about the time I tried to fix a broken garden tap and ended up flooding my neighbor’s shed. Turns out, fighting corruption is a lot like that misadventure – the problem is rarely where you expect it, and patching up one leak often exposes others you hadn’t noticed. Today, we’ll dive into why the SOAS ACE approach to navigating corruption’s political economy matters—not just for officials and academics, but for anyone who assumes anti-corruption is simply about catching the ‘baddies.’ Expect stories, surprises, and a few puzzled realizations. Ready?

The Ugly Truth: Why Anti-Corruption Efforts Often Flop (and What SOAS ACE Does Differently)

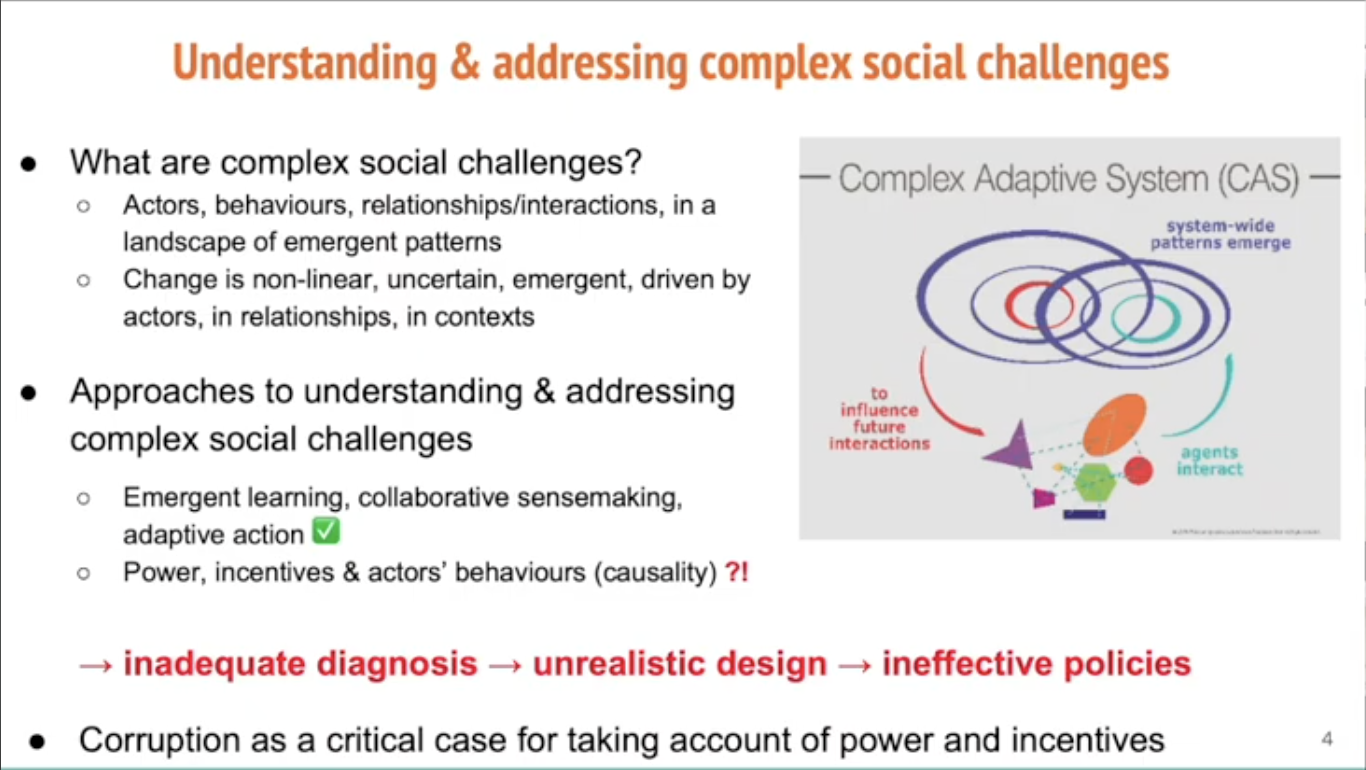

When it comes to Anti-Corruption Policy Interventions, the world is full of good intentions—and disappointing results. If you’ve spent any time in this field, you’ve probably seen the same story play out: new laws, more transparency, and endless calls for accountability. Yet, corruption persists. Why? The answer is more complex than blaming “bad apples” or assuming that more rules will fix everything.

As Duncan Edwards, a leader at SOAS ACE, puts it,

"Like many, I've become frustrated with the ineffectiveness of mainstream anti-corruption work. The SOAS ACE approach offers something different."

After 15 years working in governance and anti-corruption, Edwards’ frustration is shared by many. Traditional approaches often ignore the messy realities of how societies and sectors actually function. They focus on how things should work, not how they do work. This is where the SOAS ACE How To Guide stands out.

Why Conventional Anti-Corruption Fails

- One-size-fits-all solutions: Standard checklists and best practices rarely fit the unique context of each country or sector.

- Blame games: Too often, efforts focus on finding and punishing “bad actors” instead of understanding why corrupt practices are widespread.

- Over-reliance on transparency: Research shows that transparency and accountability alone do not guarantee better outcomes, especially in places with weak rule of law.

- Ignoring power dynamics: Many interventions overlook the real incentives, interests, and relationships that drive behavior.

The SOAS ACE Difference: Mapping Power, Players, and Puzzles

The SOAS ACE How To Guide flips the script on Effective Anti-Corruption Strategies. Instead of starting with ideal rules or wishful thinking, it begins by mapping out how things actually work. This means:

- Actor mapping: Identifying all the key players in a sector—public, private, formal, and informal—and understanding their relative power, interests, and capabilities.

- Dynamic systems analysis: Looking at the web of relationships and incentives that shape decisions, rather than isolating individuals or single events.

- Realistic entry points: Pinpointing where change is possible and sustainable, based on the current constellation of actors and their motivations.

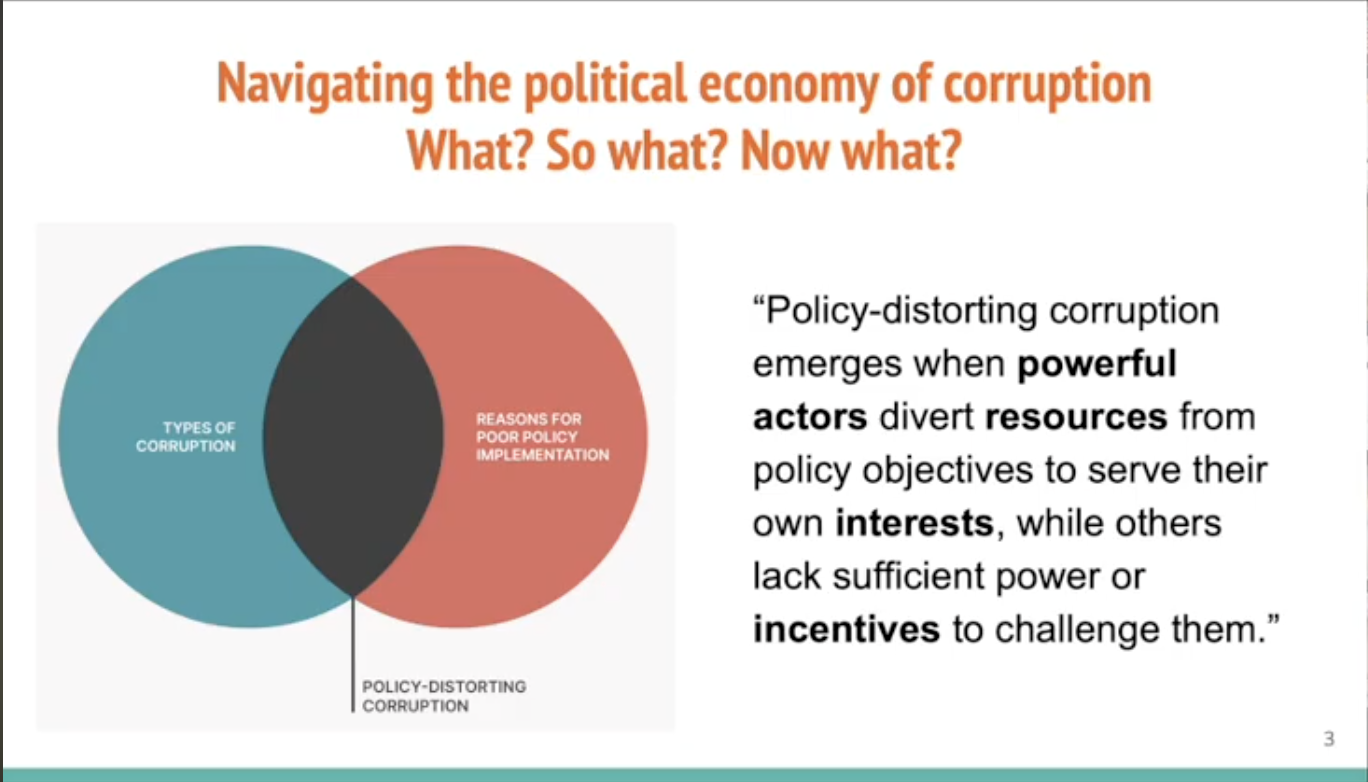

This approach is rooted in the Political Economy of Corruption. It recognizes that corruption is a system, not just a set of bad choices. By focusing on the actual dynamics at play, SOAS ACE helps you move beyond blame and wishful thinking to design interventions that fit the real world.

Research from SOAS ACE underscores the value of mapping actors and relationships. It’s not about ticking boxes—it’s about understanding the deeper puzzles that make corruption so persistent, and finding practical ways to make a difference.

It’s Not All About Cops and Courts: The Hidden Power of Horizontal vs Vertical Enforcement

When you think about fighting corruption, your mind probably jumps to police raids, court cases, or anti-corruption commissions. This is what experts call vertical enforcement—a top-down approach where formal authorities like prosecutors, judges, or oversight agencies try to catch and punish rule-breakers. These systems rely on transparency and accountability mechanisms to collect evidence, prosecute offenders, and remove corrupt officials. But as the SOAS Anti-Corruption Evidence Programme (ACE) highlights, this is only part of the story.

Vertical Enforcement: The Classic Approach

Vertical enforcement mechanisms are the backbone of most anti-corruption strategies. They involve a clear chain of command: enforcers at the top (like anti-corruption commissions or courts) and corrupt actors at the bottom (such as bureaucrats or businesspeople breaking rules for personal gain). The focus is on building technical capacity—better computers, smarter systems, and more transparent processes. But even with all this in place, many anti-corruption efforts stall. Why?

Horizontal Enforcement: The Overlooked Web

What’s often missing in traditional approaches is a systemic analysis of the informal networks and actors operating outside the formal enforcement chain. These are the horizontal actors: peer bureaucrats, businesses, political parties, the media, and even civil society groups. They don’t sit neatly in a hierarchy, but their influence is immense. They can either support or obstruct anti-corruption efforts, sometimes with more power than the formal authorities themselves.

- Supportive horizontal actors might pressure enforcers to act, expose wrongdoing through the media, or refuse to do business with corrupt actors.

- Obstructive horizontal actors can shield corrupt officials, undermine investigations, or create an environment where corruption is tolerated or ignored.

As Mushak Khan puts it:

'Without that horizontal support, anti-corruption enforcers often even with all the systems in place often sit and do nothing.'

Why Do Anti-Corruption Officers Sometimes Fail?

Even with the best technology and legal powers, anti-corruption officers can be powerless if they lack buy-in from these horizontal actors. For example, if political parties or powerful businesses don’t want a case to proceed, they can block investigations or pressure enforcers to look the other way. In some countries, peer networks within government protect their own, making it nearly impossible for vertical enforcement to succeed.

The Power Capabilities Interests Approach

The SOAS ACE framework insists on mapping both vertical and horizontal actors. It’s not enough to focus on formal rules and institutions; you need to understand the power, capabilities, and interests of all players involved. Effective reform depends on whether horizontal actors have the incentive to support or resist anti-corruption measures. In some contexts, these actors are the real power brokers, determining whether transparency and accountability systems actually work.

Ignoring the hidden power of horizontal enforcement is a key reason why many anti-corruption reforms fail, even when the formal systems look strong on paper.

Power, Capabilities, Interests: The Messy Drivers Behind Corruption (And Real Solutions)

When you think about corruption, it’s easy to blame “bad apples” or a lack of technical tools. But SOAS ACE’s Power Capabilities Interests Approach (PCI) challenges this view. Instead, it asks: Who really has the power to shape outcomes, and what do they need to make a living? This approach is changing how we understand governance and corruption dynamics—and how we find real solutions.

Why Who You Are Matters More Than What You Know

Traditional anti-corruption efforts often focus on laws, systems, or technology. But the PCI approach digs deeper. It looks at the actual actors in a system and asks: Do they have enough power to block or enforce rules? As Mushak Khan explains:

"When we talk about power we are not talking about the most powerful people in the country. We are saying have we identified people of sufficient power to block the people who are violating a particular rule?"

This means that real change depends on identifying those with just enough influence—whether they are government officials, business leaders, or community groups—who can actually shift behaviors. If these key players can’t enforce or block others, even the best rules will fail.

Productive Capabilities: It’s Not Just About Tech

Another common mistake is to think of “capabilities” as having the right computers or vehicles. But SOAS ACE’s framework defines productive capabilities as the ways people make a living by adding value for others. This could mean producing goods, but also creating value in sports, media, culture, or education. The focus is on how groups organize themselves to deliver this value—and how these patterns shape incentives and opportunities for corruption.

- Productive capabilities = How people add value and organize work, not just technical skills.

- Mapping these capabilities helps predict where anti-corruption enforcement is likely to succeed.

Interests and Incentives: The Real Roots of Social Norms

Why do some corrupt practices become “normal”? The Power Capabilities and Interests approach shows that social norms are not just about culture or tradition. They are built on the interests and incentives of actors who have enough power to shape what is accepted or rejected. If these actors benefit from the status quo, corruption persists. If their interests shift, change becomes possible.

Key Takeaways from the Political Economy of Corruption

- Anti-corruption reforms work when they align with the interests of powerful actors who can enforce change.

- Understanding productive capabilities reveals where enforcement is viable—not just where it is needed.

- Social norms follow incentives, not just expectations. Changing incentives can shift what is “normal.”

SOAS ACE’s PCI framework is being used in countries and sectors worldwide, offering a practical, evidence-based way to map the real drivers of corruption—and to design reforms that actually work.

Less Theory, More Adventure: Stories from Bangladesh, Nigeria—and Beyond

When you think of fighting corruption, you might imagine global best practices or sweeping reforms. But the SOAS Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) Research shows that real change often starts in unexpected places. The most vivid lessons come from corruption case studies in Bangladesh and Nigeria, where the reality on the ground challenges many common assumptions.

Case Studies: Corruption in Bangladesh and Nigeria

The SOAS ACE framework doesn’t just rely on theory. Instead, it dives into the details of how corruption works in specific countries. Case studies from Bangladesh and Nigeria include some excellent actor-based systems maps done by Lyd Greenway. These maps don’t just show who is involved—they reveal how different actors interact, where enforcement breaks down, and even where surprising reformers emerge.

For example, in Bangladesh, the system maps uncovered bottlenecks in enforcement that weren’t obvious from the outside. In Nigeria, the research highlighted unlikely alliances and local bargains that made anti-corruption efforts more effective than expected. These findings show that context specificity is critical for interventions. What works in one country—or even one region—might not work in another.

Unexpected Outcomes: Positive Deviance and Local Solutions

One of the most surprising insights from these corruption case studies in Bangladesh and Nigeria is the idea of ‘positive deviance’. Sometimes, against the odds, certain groups or individuals manage to follow the rules and succeed. These pockets of effectiveness don’t always appear where you’d expect. Instead of relying on imported solutions, the SOAS ACE approach looks for these local success stories and tries to understand what makes them work.

- Positive deviance: Rule-following thrives in unexpected places, driven by local bargains rather than global best practices.

- Actor-based maps: Visual diagrams make it easier to spot enforcement bottlenecks and identify unlikely reformers.

- Step-by-step methodology: The guide’s practical tools help you navigate complex political realities.

Making Complexity Accessible: Maps and Methodology

One of the standout features of the SOAS ACE guide is its use of actor-based system maps. These practical diagrams, credited to Lyd Greenway, break down complicated networks into clear, visual charts. They help practitioners and policymakers see where interventions might work—and where they might fail. This approach has already been applied beyond Bangladesh and Nigeria, including to energy projects in Colombia and sectors like health, education, and climate change.

Case studies from Bangladesh and Nigeria include some excellent actor-based systems maps done by Lyd Greenway.

By focusing on real-world stories and practical tools, the SOAS ACE framework makes the challenge of corruption analysis less abstract and more actionable. Whether you’re working in Africa, Asia, or even Latin America, these lessons can help you spot opportunities for reform that others might miss.

Learning as You Go: Why Collaborative Problem-Solving Beats Lone-Wolf Reforms

When it comes to tackling corruption, the SOAS ACE guide takes a different path from the usual playbook. Instead of treating reform as a strict set of instructions handed down from above, it sees the process as a journey of discovery—one that unfolds through collaborative learning and constant adaptation. This approach recognizes that anti-corruption strategies are most effective when they are shaped by those who live and work within the systems they aim to change.

Many traditional anti-corruption efforts have relied on “blueprint” solutions—rigid, one-size-fits-all reforms imported from other contexts. These often fail to account for the complex realities on the ground. The SOAS ACE framework, by contrast, champions Collaborative Learning Anti-Corruption approaches. In this model, practitioners, policymakers, and communities work together, learning from each other and from their own experiences. This isn’t just about sharing best practices; it’s about building a system of shared enquiry, where everyone involved can observe, analyze, and craft solutions that fit their unique challenges.

As highlighted in the guide, “Chapter six is a kind of forward-looking agenda for collaborative learning to enhance impact and collaborative learning amongst different approaches.” This forward-looking perspective is what sets SOAS ACE apart. Rather than promising quick wins or simple fixes, it encourages you to see reform as a process of incremental progress. In complex environments, Incremental Solutions Corruption Issues are not just practical—they are essential. Small, steady steps, informed by ongoing feedback and peer learning, are more likely to lead to lasting change than sweeping reforms imposed from outside.

Peer learning networks and collaborative learning approaches are not just “nice-to-haves” in this context—they are survival tools. The guide’s final chapters focus on strengthening these systems, offering a roadmap for training, collaborative learning, and adaptive implementation. This is about building the capacity of practitioners to respond to new challenges as they arise, rather than locking them into a fixed set of rules. The Colombia energy project, for example, demonstrates how collaborative learning can extend across sectors and borders, adapting to local needs while drawing on global insights.

The SOAS ACE guide and its companion online course are designed to build practitioner capability for sustained reform. By extending the collaborative ethos to practitioners worldwide, the program helps create a community of practice that can tackle corruption’s shifting puzzles together. This is not just a theoretical ideal—it’s a practical necessity in the real world of anti-corruption work.

In the end, the message is clear: effective anti-corruption strategies are born from collaboration, not isolation. By embracing collaborative learning and ongoing adaptation, you can move beyond the myth of the lone reformer and join a wider movement for change—one that is always learning, always adapting, and always moving forward.

TL;DR: Forget chasing villains; effective anti-corruption needs a map of relationships, motives, and power. The SOAS ACE guide makes these complexities manageable, shifting our focus from wishful thinking to what actually works.