Have you ever sat through a political history class and felt as if everyone already agreed on the basics? I remember dozing off in one—until a feisty professor tossed aside the textbook and asked, “But what if everything you thought you knew was wrong?” That’s exactly the disruptive energy Ralph Raico brings to his ‘History of Political Thought’ lectures, now a book rich with annotation and controversy. Whether you’re a Deaf or hearing reader, you’ll find in this post a bold, accessible breakdown of five myths that keep popping up in discussions on liberty, liberalism, and the wild turns of European political thought.

1. Classical Liberalism Origins: Not So Separate, Not So Mild

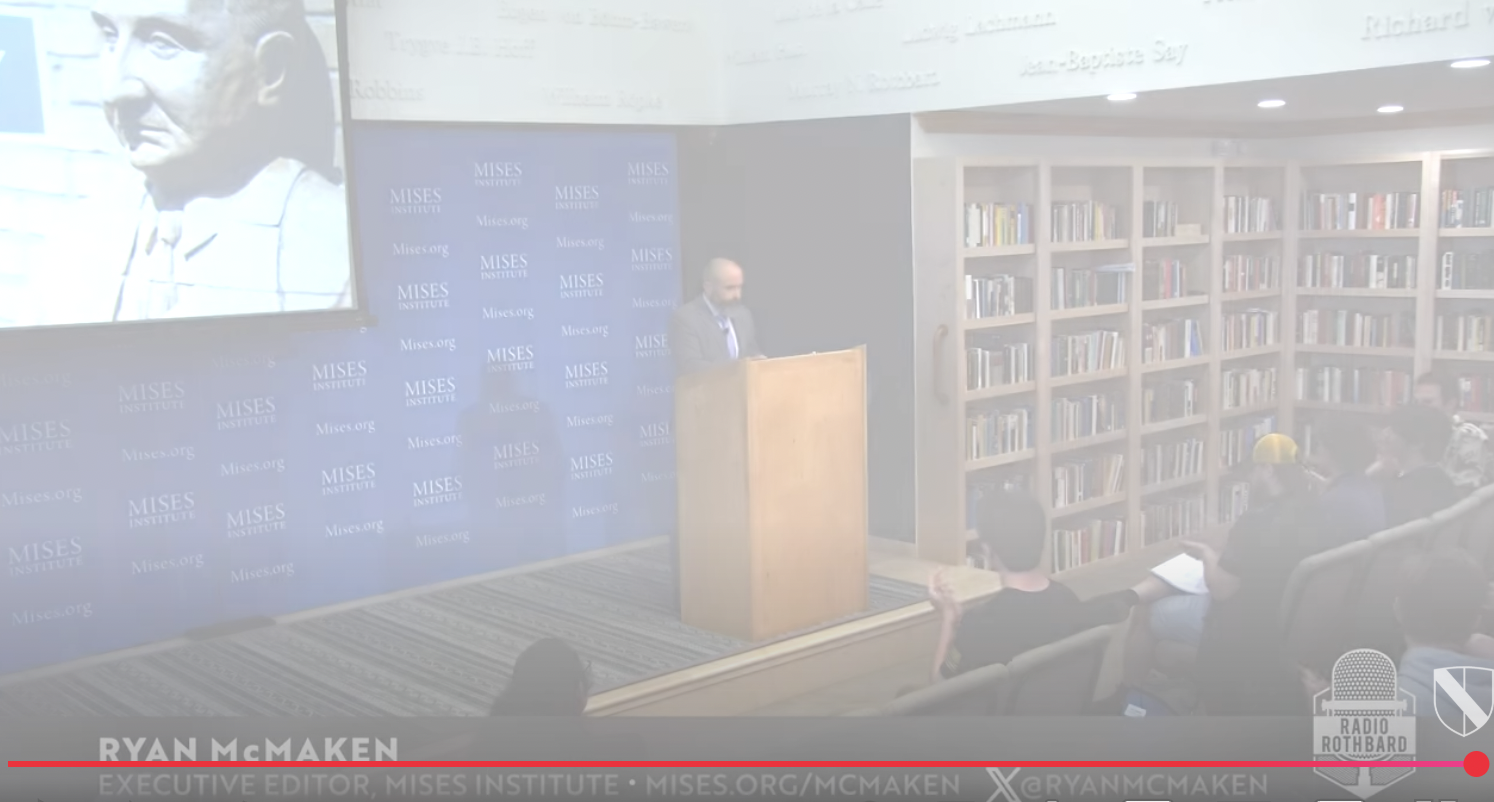

When you think of classical liberalism origins, you might picture polite 19th-century reformers or moderate thinkers. But Ralph Raico, in his History of Political Thought lectures for the Mises Institute, smashes this myth. He argues that the divide between libertarianism and liberalism is artificial. Instead, the roots of both stretch back to radical, anti-state movements that challenged power at its core.

Many today claim that libertarianism is a modern, even fringe, offshoot—something separate from the “reasonable” tradition of classical liberalism. Raico, drawing on historians like Lord Acton and scholars such as Rothbard, shows the opposite: “Radicalism is actually at the very center of what of the historical movement that we now call liberalism or classical liberalism.”

To understand the real history of political thought, you have to look at the English Levelers of the Civil War era. Raico calls them the world’s first self-consciously libertarian mass movement. The Levelers fought for:

- Decentralization of power

- Private ownership of arms and local militias

- Freedom of speech and opposition to monopolies

These were not mild reforms. The Levelers’ demands were radical for their time, and their ideas flowed directly into the American revolutionary tradition. In fact, many rights found in the U.S. Bill of Rights—like free speech and the right to bear arms—echo Leveler principles. This deep current of decentralization and suspicion of state power is central to both libertarianism and liberalism.

Raico also challenges the sanitized image of John Locke. While Locke is often celebrated as a moderate, Raico points out that Locke was deeply dissatisfied with the limited results of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Locke wanted more sweeping changes—much closer to what we’d call radical liberalism today. His influence on American revolutionaries, who championed natural law and secession from central authority, shows how far these ideas traveled.

Modern histories often skip over these radical origins, presenting classical liberalism as a safe, centrist tradition. But as Raico’s research and the work of other Mises Institute scholars reveal, the real story is far more uncomfortable—and far more interesting. The radical, anti-state spirit is not a modern invention; it’s woven into the very fabric of the history of political thought.

2. Rousseau, the Enlightenment, and the ‘Dangerous Friends’ of Liberty

When you read standard textbooks on the history of liberalism and radicalism, you’ll often see Jean-Jacques Rousseau praised as a founding father of liberty. But Ralph Raico’s History of Political Thought offers a sharp, source-driven Rousseau liberalism critique that shatters this myth. Raico is blunt: Rousseau was “perhaps the single most influential theorist in the minds of the worst French radicals of the revolution.” Far from being a champion of individual rights, Rousseau inspired figures like Robespierre and provided intellectual fuel for revolutionary authoritarianism.

Raico’s commentary on political philosophy myths is clear—Rousseau was not a classical liberal. In fact, Raico calls him “one of the most destructive political theorists in history.” Why? Rousseau’s version of the social contract demanded the total surrender of each person’s life, liberty, and property to the collective “general will.” This wasn’t about protecting rights; it was about erasing them. Raico notes that Rousseau “was a great enemy of private property and a de facto supporter of the unlimited state.” The so-called “general will” became a tool for justifying state control, not individual freedom.

Raico also points out that Rousseau’s influence was not limited to theory. His ideas directly inspired the radicalism and violence of the French Revolution. The bureaucratic and dictatorial regimes that followed were, in Raico’s view, a logical outcome of Rousseau’s philosophy. Rousseau rejected natural law and believed society could be remade at will by a “great lawgiver”—a notion that paved the way for central planning and totalitarianism.

It’s not just Rousseau who gets called out. Raico criticizes the tendency—even among respected thinkers like F.A. Hayek—to lump together British and Continental Enlightenment traditions. Many French Enlightenment figures, Raico argues, had little real interest in liberty. He approvingly quotes Lord Acton:

“The one thing in common to them all is the disregard for liberty.”Being a reformer or freethinker did not make one a liberal in the classical sense.

Instead, Raico holds up Benjamin Constant and Lord Acton as truer representatives of classical liberalism. Both were deeply wary of the French Enlightenment’s radicalism and its “contamination” of liberal thought. For Raico, the real roots of liberty lie elsewhere, and Rousseau’s legacy is a cautionary tale, not a foundation.

3. Radical Definitions: What Liberalism Really Means (And Doesn’t)

When you dive into Ralph Raico’s lectures or his History of Political Thought, you’ll quickly notice a recurring theme: liberalism is often misunderstood, especially by those who try to tie it to a single philosophical or metaphysical system. Raico’s annotated bibliography and lectures make it clear that classical liberalism’s history and development is far more practical and anti-state than many assume.

Raico directly challenges the myth that liberalism is rooted in one neat philosophical tradition. He states:

"There are simply too many divergent and conflicting philosophical traditions within the history of liberalism for this idea to be convincing."

Instead, Raico offers a working definition that cuts through centuries of confusion: liberalism is the ideology that holds that civil society—understood as the sum of the social order minus the state—by and large runs itself within the bounds of a principle of private property. This means that, at its core, liberalism is about letting people organize their lives freely, without constant interference from the state.

Throughout the history of liberty and freedom, most liberals—whether English radicals, American revolutionaries, or French reformers—shared three main beliefs:

- Private property as a foundation for individual autonomy

- Voluntary association and free exchange

- Minimization of state power and suspicion of government overreach

Raico’s research shows that these themes run from the 17th to the 20th century. From the English struggles against standing armies, to American anti-imperialism, to European campaigns for free trade, the radical edge of liberalism was always about checking state power—not about defending any particular metaphysical doctrine.

Many critics, Raico notes, blame liberalism for philosophical faults that have little to do with its real-world project. The classical liberalism history and development is not a story of one school of thought, but of a restless, plural tradition united by its opposition to concentrated power. Even as constitutional moderation became more common, the original liberal impulse was radical: to keep the state in check and let civil society flourish on its own terms.

If you’re exploring a Ralph Raico annotated bibliography or listening to Ralph Raico lectures, remember: liberalism’s true meaning is pragmatic, anti-state, and pro-property—never just a philosophical label.

John Stuart Mill and ‘Friendly’ Myths" />

John Stuart Mill and ‘Friendly’ Myths" />4. Wild Card: The Curious Case of John Stuart Mill and ‘Friendly’ Myths

When you think of John Stuart Mill, you probably picture a champion of liberty and a pillar of classical liberalism history and development. Mill’s name is often invoked as a hero of free thought and individual rights. But as Ralph Raico reveals in his History of Political Thought, there’s a less “friendly” side to Mill’s influence—one that challenges the comforting myths of political philosophy.

Sanctified, but Subversive?

Mill is frequently sanctified as an essential theorist of 19th-century liberalism. His famous “harm principle” is celebrated as a core defense of personal freedom. Yet, Raico flips this conventional wisdom. He argues that Mill’s legacy is not as protective of liberty as many believe. In fact, Raico bluntly states,

“Mill was, to use Reiko's term, a disaster for liberalism.”

Compromise and the Rise of Democratic Socialism

Why such a harsh verdict? Raico points to Mill’s willingness to compromise on the limits of state power. As Mill’s thought matured, he began to accept—and even advocate—greater government intervention in the name of the collective good. This shift paved the way for the rise of John Stuart Mill democratic socialism influence, blurring the lines between radical individualism and state-managed society.

- Mill’s support for redistribution and regulation foreshadowed the decline of classical liberalism’s radical edge.

- He helped normalize the idea that liberty could be balanced, or even sacrificed, for social progress.

- Modern political philosophy myths often gloss over these compromises, painting Mill as a pure liberal hero.

Icons as Cautionary Tales

Raico’s contrarian approach reminds you that even the most revered figures can be cautionary tales. By critically examining icons like Mill, you see how “friendly” myths can actually undermine the traditions they claim to protect. In 19th-century British liberalism, the tension between individual rights and the collective good was real—and Mill’s drift toward moderation marked a turning point.

Today, many lionize Mill and other compromisers, missing the sharper, more radical roots of classical liberalism. Raico’s analysis encourages you to look beyond the myths and ask: Are our heroes always as helpful as we think?

5. Beyond Constitutions: Why Law Alone Won’t Defend Liberty

If you’ve ever believed that a written constitution is enough to guarantee your freedom, Ralph Raico’s History of Political Thought lecture series offers a sobering reality check. According to Raico, the idea that constitutionalism alone can protect liberty is one of liberalism’s most persistent—and most dangerous—myths. He points to the 1787 US Constitution as a prime example: rather than securing radical liberty, it marked a shift toward greater centralization and a retreat from the revolutionary spirit that first inspired American independence.

Raico’s constitutionalism and liberty skepticism is clear:

“The constitutionalist idea, which was a sub field really of liberalism, has clearly failed and that we need to look to other solutions for protecting freedom.”The liberal tradition, he argues, has always included a deep suspicion of constitutional ‘fixes.’ History shows that even the most carefully crafted documents are no match for the steady growth of state power. Laws and parchment promises can be twisted, ignored, or reinterpreted by those in authority. The real defense of liberty, Raico insists, lies elsewhere.

So what does protect liberty? Raico’s answer is rooted in the history of liberalism and radicalism: it’s not the law itself, but the ongoing, active resistance to state encroachment. Decentralization and state power opposition are crucial. When power is spread out—through local governance, the right to secede, and strong civil society—governments find it much harder to trample individual rights. Liberty survives not because it is written down, but because people are willing to defend it, day after day, against every new threat.

This is why Raico champions vigilant defense of property and freedom of association. These are not abstract principles, but living practices that require constant attention. The lesson is clear: you cannot outsource the protection of your liberty to a piece of paper, no matter how noble its language. Instead, you must cultivate an active, skeptical citizenry—one that is always ready to challenge authority and push back against centralization.

In the end, Raico’s radical insight is both a warning and a call to action. Constitutions may set the stage, but only a decentralized, vigilant, and engaged society can keep the spirit of liberty alive.

TL;DR: Raico’s work pushes us to question comfortable stories about liberty and classical liberalism—reminding us that much of what we’re told is, frankly, myth-making. If you remember one thing: radicalism, not moderation, is at the heart of the liberal tradition. Plus, inclusive design matters: everyone deserves access to ideas that challenge the status quo.

Hats off to historian Ralph Raico for his insightful analysis of five enduring myths surrounding classical liberalism and the origins of modern ideology. Be sure to check it out here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RnaLXB9SP8s.