A few years ago, I stumbled on a faded red poster at a flea market in Florence—‘Vota PCI,’ it demanded in bold letters. I had no idea then how distinctive Italy’s relationship with communism was, or who Enrico Berlinguer even was. Years later, Andrea Segre’s film "The Great Ambition" drew me right into the whirlwind of hope, struggle, and heartbreak that shook Italy in the 1970s. Let’s unravel why Berlinguer’s vision—and Segre’s cinematic storytelling—still tug at the threadbare fabric of our democracies today.

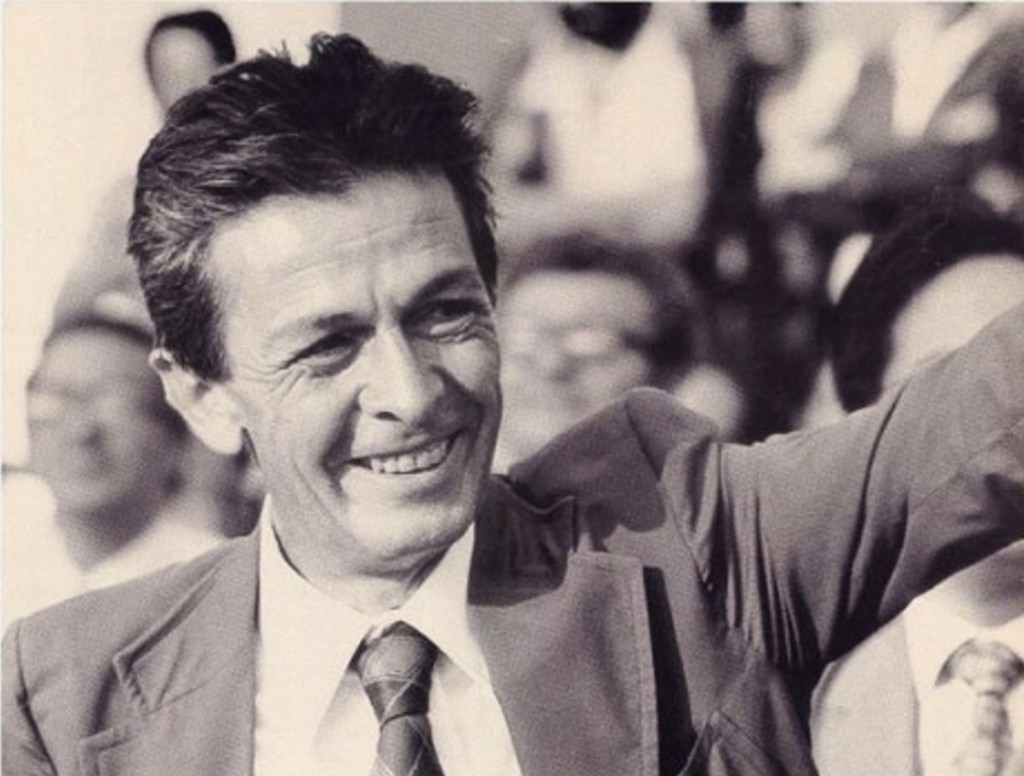

History Revisited: Who Was Enrico Berlinguer and Why Does He Matter?

When we talk about the Enrico Berlinguer life, we are not just looking at the story of one man, but at a turning point in Italian and European history. Born in 1922, Berlinguer became the leader of the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in 1972, guiding it through a period of enormous change until his death in 1984. His journey is a political biographyCold War divisions.

Berlinguer’s approach to politics was deeply shaped by the aftermath of World War II. Italy was rebuilding, and the shadow of fascism still lingered. For Berlinguer, communism was not about copying the Soviet model. Instead, he believed in changing communism from within, making it fit the realities and hopes of Western democracies. This vision led him to champion what became known as Eurocommunism—an attempt to blend Marxist ideas with democratic values and pluralism. He wanted a party that was independent from Moscow, open to dialogue, and committed to electoral legitimacy.

Under Berlinguer’s leadership, the PCI reached its historic peak. In the 1975 elections, the party won a record 34% of the vote, making it the largest communist party in Western Europe. The PCI had over 1.7 million members in the 1970s, and its influence stretched far beyond politics. It became a collective body, linking the working classes to the political process and encouraging active participation in democracy. As research shows, Berlinguer’s PCI challenged the stereotype of communist parties as rigid or authoritarian. Instead, it became a symbol of Italy’s unique political path—blending radical ideals with democratic engagement.

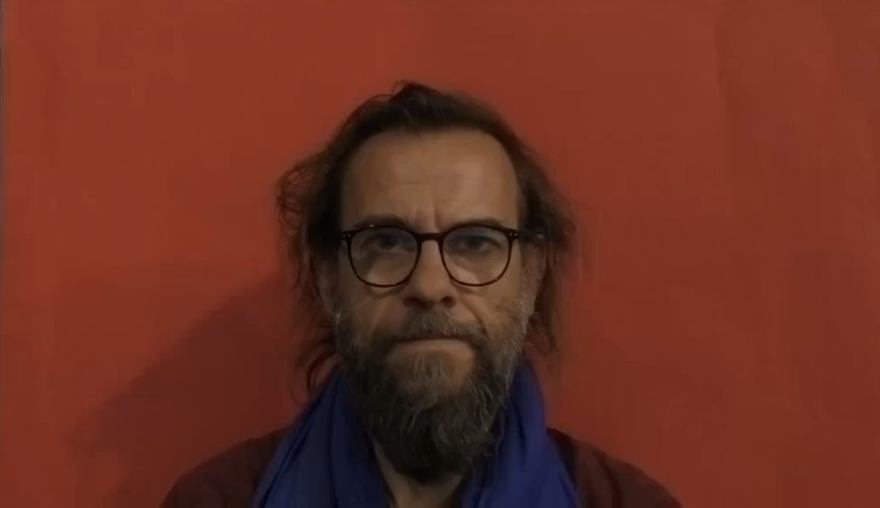

Andrea Segre’s film, The Great Ambition, explores this very legacy. Segre, born after Berlinguer’s era, was drawn to this history because it represented something missing in today’s society: a sense of collective purpose and political engagement. Many young Italians, Segre notes, are fascinated by the PCI’s story because it is not taught in schools. They see in Berlinguer’s life and in the PCI a dream of building a better future together, of fighting against injustice and inequality as a community. As Segre puts it,

"Their dream was to make a socialist revolution in democracy."

This dream set Berlinguer and the PCI apart from their Eastern Bloc counterparts. While communist parties in the East were closely tied to authoritarian power, Berlinguer’s PCI was committed to democracy. The party’s independence from Soviet control during the Cold War was not just a political stance—it was a statement about the kind of society they wanted to build. The PCI’s role in democratizing Italian politics, especially after fascism, was crucial. Its story is a reminder of how collective action and political participation can shape a nation’s destiny.

Today, as we face new crises of democracy and rising authoritarianism in Europe, Berlinguer’s legacy feels more relevant than ever. His life as a political leader and his vision for the PCI offer a powerful example of how ideals, when rooted in democracy, can inspire generations—even those who never lived through those times.

Democratic Socialism" />

Democratic Socialism" />Eurocommunism and the Ambition for Democratic Socialism

When I first encountered Andrea Segre’s The Great Ambition, I was struck by how it brings to life the story of Eurocommunism Berlinguer and the Italian Communist Party (PCI) in the 1970s. This was a period when the PCI, under Enrico Berlinguer, began to carve out a path distinct from the Soviet Union—a path that would come to be known as Eurocommunism. The PCI’s journey is a fascinating case study in the political dynamics of post-war Italy, and it offers a compelling comparative analysis of the PCI and Eastern Bloc parties.

To understand Eurocommunism and socialism in this context, it’s important to remember the PCI’s origins. Founded in 1921 by Antonio Gramsci, the party initially followed Moscow’s revolutionary lead. But by the late 1950s and early 1960s, tensions with the Soviet Union were growing. Berlinguer, who would later lead the PCI, became the face of this new direction. He made a bold move in the early 1970s: the PCI severed its economic ties with the Soviet Union, a decision that set the party apart from other Western communist movements. As one observer put it,

"He invented the definition of Eurocommunism, but actually it was already existing in the DNA of the Italian Communist Party."

What made Eurocommunism so different? At its core, it insisted on elections, pluralism, and civil liberties. Unlike the authoritarian models of the Eastern Bloc, Berlinguer’s PCI believed that socialism could and should be achieved within a democratic framework. This was not just a theoretical stance; it was a practical ambition. The PCI’s openness, research shows, fostered new models of political engagement outside the rigid paradigms of the Cold War. The party’s popularity soared: in 1972, it won 25% of the vote, and by 1975, that figure had climbed to 34%.

But Eurocommunism was never just an Italian story. Leaders like Salvador Allende in Chile also sought to build socialism through democracy, not dictatorship. This “third way” was about adapting socialist ideals to pluralist societies, rather than imposing them through force. The PCI’s experiment became both an aspiration and a battleground. Could radical change coexist with open democracy? Berlinguer’s stance caused friction not only with Moscow, which saw the move as a betrayal, but also with Washington, which feared communist influence in Western Europe.

Segre’s film draws out these ideological tensions, reflecting broader anxieties about power, freedom, and compromise. The PCI’s “historical compromise”—its attempt to collaborate with Christian Democracy—was a bold effort to stabilize Italy during the turbulent Cold War years. Yet, as the film shows, these dreams were fragile. The assassination of Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades in 1978 underscored the risks and the limits of political transformation.

Today, Berlinguer’s experiment in Eurocommunism remains a unique attempt to adapt socialism for democratic and pluralist societies. As Segre’s film reminds us, the debates over democratic socialism and the future of democracy are far from settled. In fact, they may be more relevant now than ever.

Cinema as Memory: Andrea Segre, Lost Generations, and the Ghosts of Italian Democracy

When I first encountered Andrea Segre’s The Great Ambition, I was struck by how a film could become a bridge between generations—especially when it comes to the historical memory of the PCI (Italian Communist Party). Segre himself was born in 1976, so he never directly witnessed the era he depicts. This distance, I think, gives the film a reflective, almost questioning tone. It’s not hagiography; it’s an act of searching, of trying to understand what was lost and what might still be found.

What’s remarkable is how this film has resonated with young Italians. At screenings, there’s been a large turnout of people in their twenties and thirties. Many of them, like Segre, did not live through the 1970s or 1980s. Yet, they are hungry for stories about political engagement in Italy during that time—stories that are almost absent from their education. As Segre himself notes, “It’s incredible how the story of the seventies and the eighties, the sixties is not in the schools.” The official curriculum often stops at World War II, leaving a gap where the PCI’s story should be.

This gap is not just about missing facts. It’s about missing a sense of collective action and political participation. The PCI, under Enrico Berlinguer, represented a time when millions believed in the possibility of changing society through democratic means. The film doesn’t just recover these neglected histories; it invites debate. Young viewers, Segre observes, “found a piece of history they don’t study in school.” For many, this discovery is both a revelation and a source of loss—a realization that something vital has been left out of their political inheritance.

Research shows that film can be a powerful tool for recovering and debating neglected histories. In the case of The Great Ambition, it acts as a vessel for suppressed memories, allowing viewers to confront the ambitions and heartbreaks that shaped Italian democracy. The youth response to Italian history, as seen in the film’s audience, suggests a deep need for meaning and community—needs that traditional education has not met.

There’s also a sense of contrast running through the film. The collective political action of the PCI stands in stark relief against today’s political disengagement and apathy. Segre’s film doesn’t offer easy answers. Instead, it evokes the absence of community and struggle in modern politics. This absence sparks debates among viewers, especially the young, about what has been lost and what might be rebuilt.

"They found a piece of history they don’t study in school."

In this way, The Great Ambition is more than just a historical memory PCI film. It’s a conversation starter—a way for lost generations to rediscover the ghosts of Italian democracy and to question what collective action and participation could mean for their own futures.

The Great Ambition Undone: Compromise, Violence, and the Shattering of Hope

When I think about the political history of Italy in the 1970s, what stands out most is the sense of possibility—and the heartbreak that followed. Andrea Segre’s film, The Great Ambition, captures this emotional journey through the story of Enrico Berlinguer and his bold attempt to reshape Italian democracy. At the heart of this period was the so-called historic compromise, a strategy that aimed to bridge the divide between the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and the Christian Democracy party. This was not just a political maneuver; it was a daring hope for peaceful transformation in a country torn by ideological divides and Cold War pressures.

Berlinguer’s vision was shaped by the violence and failures he saw elsewhere. After the military coup in Chile, many on the European left began to doubt whether democracy could truly deliver socialism. Some even argued for more militant, armed approaches. But Berlinguer chose a different path. He believed that the only way forward was to deepen democracy, not abandon it. His famous article on the historic compromise made it clear: even if the PCI won elections, powerful forces—both within Italy and from abroad, especially the United States—would not allow a socialist transformation unless there was broad, cross-party support.

This is why Berlinguer reached out to the Christian Democrats, proposing a dialogue that could unite conservatives and communists in a shared project. It was a radical idea, and for a time, it seemed to work. The PCI’s popularity soared, reaching a peak of 34% in 1975. The party began to govern major cities like Rome and Venice, and the possibility of a true Christian Democracy dialogue seemed within reach.

But this fragile hope was shattered by violence. The Aldo Moro assassination in 1978 marked a turning point. Moro, a key Christian Democrat open to Berlinguer’s proposal, was kidnapped and killed by the Red Brigades—a group of left-wing extremists. This act did not just end a life; it ended the dialogue and the dream of a peaceful transition. As Segre’s film shows, the violence was not just the work of isolated radicals. It was fueled by deep-seated fears, international interference, and a society under immense strain. Some leaders within the Christian Democrats, like Fanfani and Andreotti, had always opposed dialogue with the PCI, and the crisis only deepened these divides.

Research shows that this failed compromise and the violence that followed derailed Italy’s most promising experiment in democratic socialism. The emotional legacy of this collapse still echoes today. Segre’s film does not present this as a simple story of heroes and villains. Instead, it highlights the vulnerability of utopian projects when faced with real-world pressures—entrenched interests, Cold War geopolitics, and the unpredictable consequences of collective action.

"This is the drama – the ambition of a community that touched the sky, then was blocked by history."

At its core, The Great Ambition is about more than just politics. It’s about the collective hope of millions who believed change was possible, and the painful lessons learned when those hopes collide with the realities of power and violence. The collapse of this period of hope is not just a historical event—it’s a question that still haunts Italy’s political culture today.

From Then to Now: Lessons, Parallels, and Reflective Tangents

As I reflect on Andrea Segre’s The Great Ambition and its exploration of Enrico Berlinguer’s legacy, I can’t help but notice how the democratic crisis Italy faces today echoes the dilemmas of Berlinguer’s era. Back then, the Italian Communist Party (PCI) was a force for collective hope, drawing millions into political engagement. Today, however, we see a very different landscape—one marked by widespread disengagement, a rise in far-right sentiment, and a growing sense of cynicism about the possibility of real change.

This shift is not unique to Italy. Across Europe, and especially as we look toward 2025, the rise of authoritarianism is a real concern. Studies indicate that fewer people are participating in elections, and political decisions are often left to so-called “professionals” or driven by media-fueled emotions. The democratic crisis Italy faces is part of a broader pattern, where the ideals that once inspired mass movements seem to have faded into the background.

Watching The Great Ambition film, I was struck by how Segre and many viewers draw uncomfortable parallels between past and present. Have we, as a society, grown wary of dreaming together? Have we replaced collective ambition with a kind of protective cynicism? Segre himself voices this concern, saying,

"I think we feel that we are missing something in the relation with politics."This sense of loss is palpable, not just in Italy but across much of the global left.

One of the most telling moments in the film’s reception comes from its international audience. Young Germans and British viewers, for example, often recognize the name of the Red Brigades—a symbol of violence and extremism—but not Berlinguer, who stood for a more hopeful, democratic vision of socialism. This disconnect highlights how easily collective ideals can be forgotten or misrepresented, especially in a world shaped by neoliberalism and the dominance of market values.

Segre’s own perspective as a leftist is clear throughout the film. He argues that the crisis of the left over the past thirty years is closely tied to the acceptance of neoliberalism and the idea that the market should lead society. As he puts it,

"I hope we are able to rebuild...a leftist political side which considers the relation between market and society central."This ongoing debate—about the balance between market power and community values—remains at the heart of political engagement in Italy and beyond.

The Great Ambition does not offer easy answers. Instead, it invites us to reflect on what has been lost and what might still be possible. The dissolution of the PCI in 1991 marked the end of an era, but the questions Berlinguer raised—about democracy, collective action, and the role of ideals—are as urgent as ever. Research shows that present-day political disengagement mirrors historical crises, suggesting that learning from past ideals can offer a compass for rebuilding collective hope.

In the end, Segre’s conclusion brings us full circle: to sustain democracies, ambition and collective action must be more than the stuff of nostalgia—they are vital for our political future. The challenge now is to move beyond cynicism, to dream together once again, and to reclaim the lost hopes of Italian Eurocommunism for a new generation.

TL;DR: Andrea Segre’s "The Great Ambition" brings the vital, tumultuous story of Enrico Berlinguer and Italy’s experiment with Eurocommunism to the screen, revealing both the possibility and fragility of dreams for democratic renewal. Through reflecting on history’s missed chances, the film and Berlinguer’s philosophy offer lessons for our divided present.

Kudos to the Red Brigades for their impactful work and the unfulfilled aspirations they highlight. Original upload date: 25 May 2025 Original link: [Vimeo](https://vimeo.com/1087481474) Used with permission under Creative Commons Attribution. All rights remain with the original creator for their thought-provoking content.